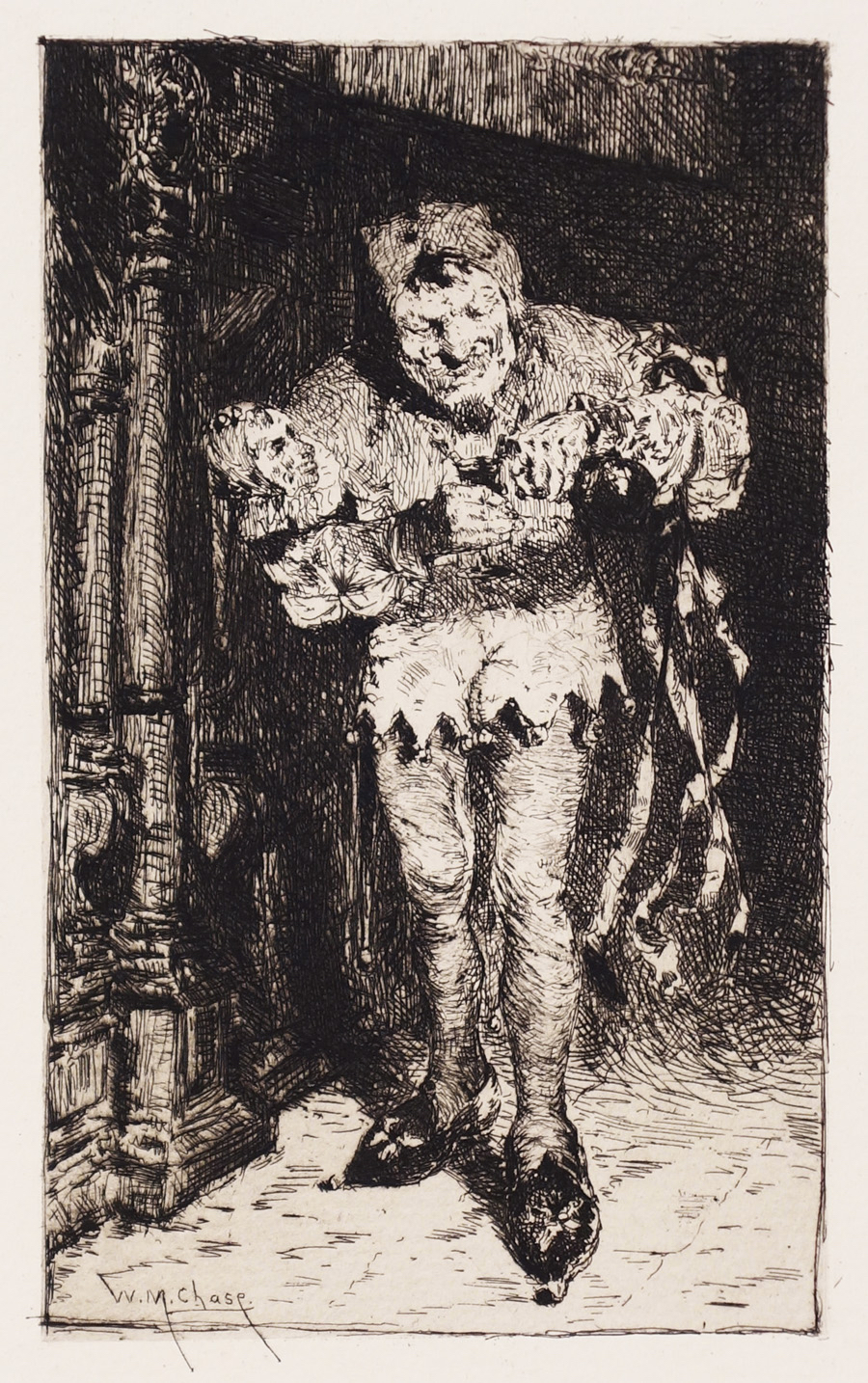

In conjunction with a Museum Studies class project in spring 2020 at Gustavus Adolphus College, the Hillstrom Museum of Art has acquired an 1879 etching by American artist William Merritt Chase (1849-1916) titled Keying Up—The Court Jester. The prolific artist, acclaimed for his Impressionist approach, was also a leading teacher of a generation of American artists through his Chase School of Art in New York (founded in 1896 and today the Parsons School of Design). Born in Ninevah, Indiana, not far south of Indianapolis, Chase as a young man studied at the National Academy of Design in New York before heading to the Academy of Fine Arts in Munich, then a destination rivalling Paris for Americans wishing to study art abroad.

While still in Germany, the artist painted his 1875 oil depiction of a Court Jester (Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art), the basis of the etching. The painting was one of several jester images for which Chase used the same model. He recounted that the man in the jester outfit greatly enjoyed alcoholic beverages and once, during a break from modeling, drank the contents of a whiskey bottle in the studio only to discover that it was hair tonic Chase had stored in there—which led to him no longer modeling for the artist. The Court Jester painting brought Chase wide-spread attention when it won a medal in the Philadelphia 1876 Centennial Exhibition, and Chase’s print—which is very similar to the painting, albeit in reversed imagery—seems to have been created to further spread his fame. The etching was widely available, including by being published in 1881 in The American Art Review. That short-lived but influential publication included original etchings in its monthly issues and was instrumental in supporting etching as the art form at the heart of the “American Etching Revival.”

This Revival was a movement in which etching became popular as a medium for creating original works of art (rather than for reproducing paintings by other artists). Etching, which has for many years been taught at Gustavus, is done by tooling an image through a protective coating on a metal plate, after which the plate is immersed in acid. The acid corrodes—or etches—the exposed lines on the plate to create grooves. A print is made by forcing ink into the groves and pressing a sheet of paper against the plate, resulting in an ink image on paper of the etched design.

The etching technique for printmaking had been known since 1515 or earlier, and Dutch artist Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669) had been a prolific master of the medium. Although etching fell out of favor, it was revived in the 19th century, first in France and England, then in the United States. There, it was centered around the formation in 1877 of the New York Etching Club. That group, and similar clubs in other major American cities, promoted the ideal of the peintre-graveur, a French term that translates as “painter-etcher” and indicates an artist who makes etchings as original works of art (rather than as reproductions of artworks by others). The American Etching Revival was a phenomenon that saw many artists, females prominent among them, avidly pursuing the medium. The veritable craze eventually led to the wide-spread trope of a salacious man attempting to seduce an innocent woman by asking her to “come up and see my etchings.” Although etching never completely waned again, the first wave of its revival in America was relatively short-lived, lasting only around a quarter century.

Chase was one of the 17 original members of the New York Etching Club. Its inaugural meeting featured an etching demonstration at the New York studio of artist James David Smillie (1833-1909), during which an etching plate prepared by Robert Swain Gifford (1840-1905) was printed on a press by Leroy Milton Yale (1841-1906); all of these artists are also represented in the Hillstrom Museum of Art’s collection. Unlike many etchers, such as Smillie, Yale, and Gifford, Chase was not very prolific in the medium, making only about 10 different etchings (versus the hundreds of paintings from his hand), and Keying Up—The Court Jester is arguably his most important effort.

The Museum’s example of Keying Up is in fine condition. It is signed in the plate “W. M. Chase,” visible in the lower left of the image. American Etching Revival prints are considered especially desirable if they are also signed by their artists in pencil in the sheet margins outside of the printed plate area. However, none of the known examples of Keying Up—including those in the collections of the National Gallery of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (both in Washington, DC), the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Minneapolis Institute of Art—have such an added signature, and it’s unlikely that Chase signed any in pencil.

Chase’s etching was selected from among a group of American Etching Revival works presented as possible Museum acquisitions by students in the College’s spring 2020 Museum Studies class. Each class member located an available etching by an artist not already represented in the Museum’s collection, then attempted to make persuasive arguments as to why that etching should be acquired. Following the presentations, a ballot was held, with each student voting for the top two choices. The Chase print was presented by class member Gigi deGrood (’22), a studio art major. Her selection and another, an 1887 Stephen James Ferris (1835-1915) etching titled A Good Story presented by communications major Ingrid Rischmiller (’21), received the same number of student votes, so a tie-breaking vote was cast by the Museum director and class instructor.

All of the works presented for the Museum Studies project would have been fine acquisitions, and they included works selected by history major Cullen Osen (’20), by intended art history and studio art double major Annalise Schaaf (’23), and by art history and management double major Kari Steen (’21). However, the Chase work is particularly appealing, given that Museum namesake Richard L. Hillstrom once owned a landscape by the artist. That oil painting was given by him to the Minneapolis Institute of Art in 1980 in exchange for an annuity. The Institute sold the Chase painting at auction in New York in 1981 and Hillstrom was pleased to be able to report that it used the proceeds to endow its Richard Lewis Hillstrom Fund for acquisitions.

Keying Up—The Court Jester joins around 35 American Etching Revival prints in the Hillstrom Museum of Art’s collection (see below for several examples), including works by prominent female etchers such as the famous Mary Nimmo Moran (1842-1999), Jennie Augusta Brownscombe (1850-1936), Edith Loring Getchell (1855-1940), and Gabrielle de Vaux Clements (1858-1948). A future exhibition of all the American Etching Revival works in the Museum is being planned, and it will include the newly-acquired print by Chase as well as several other etchings purchased in conjunction with earlier iterations of the annual Museum Studies class.

IMAGE CAPTIONS:

Main image:

William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), Keying Up—The Court Jester, 1879, etching on paper, 5 7/8 x 3 9/16 inches, Hillstrom Museum of Art purchase with endowment acquisition funds

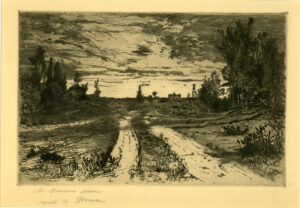

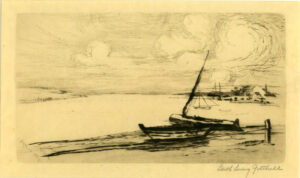

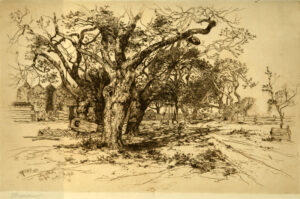

Additional images (left to right, top to bottom):

Mary Nimmo Moran, (1842-1899), Twilight, East Hampton, 1880, etching on paper, 7 15/16 x 11 3/4 inches, Hillstrom Museum of Art purchase with endowment acquisition funds

Stephen Parrish, (1846-1938), Powerville, 1884, etching on paper, 5 3/16 x 9 7/8 inches, gift of Carol and James Goodfriend in honor of the Reverend Richard L. Hillstrom

James Abbott McNeill Whistler, (1834-1903), Long Venice, 1879-1880, etching printed on fine cream laid paper, 5 x 12 1/4 inches, Hillstrom Museum of Art purchase with endowment acquisition funds

Gabrielle de Vaux Clements, (1858-1948), A New England Road, 1883, etching on paper, 5 3/4 x 7 7/8 inches, Hillstrom Museum of Art purchase with funds donated by Dawn and Edward Michael

Charles Adams Platt, (1861-1933), Mud Boats on the Thames, 1883, etching on paper, 6 1/8 x 11 inches, gift of Joni and Don Myers

Edith Loring Getchell, (1855-1940), Beached Skiffs at Salem, May 26, 1887, 1887, etching and drypoint on paper, 7 x 12 inches, Hillstrom Museum of Art purchase with endowment acquisition funds

Edith Penman, (1860-1929), Round Landscape, 1890, etching on paper, 6 7/8 inches in diameter, Hillstrom Museum of Art purchase with endowment acquisition funds

Thomas Moran, (1837-1926),Mulford’s Orchard, East Hampton, September 21, 1883, 1883, etching on paper, 12 x 17 3/4 inches, gift of Dr. David and Kathryn Gilbertson

Robert Swain Gifford, (1840-1905), Near the Coast, 1885-1886, etching on paper, 8 5/8 x 12 inches, gift of Rona Schneider Prints

Leave a Reply